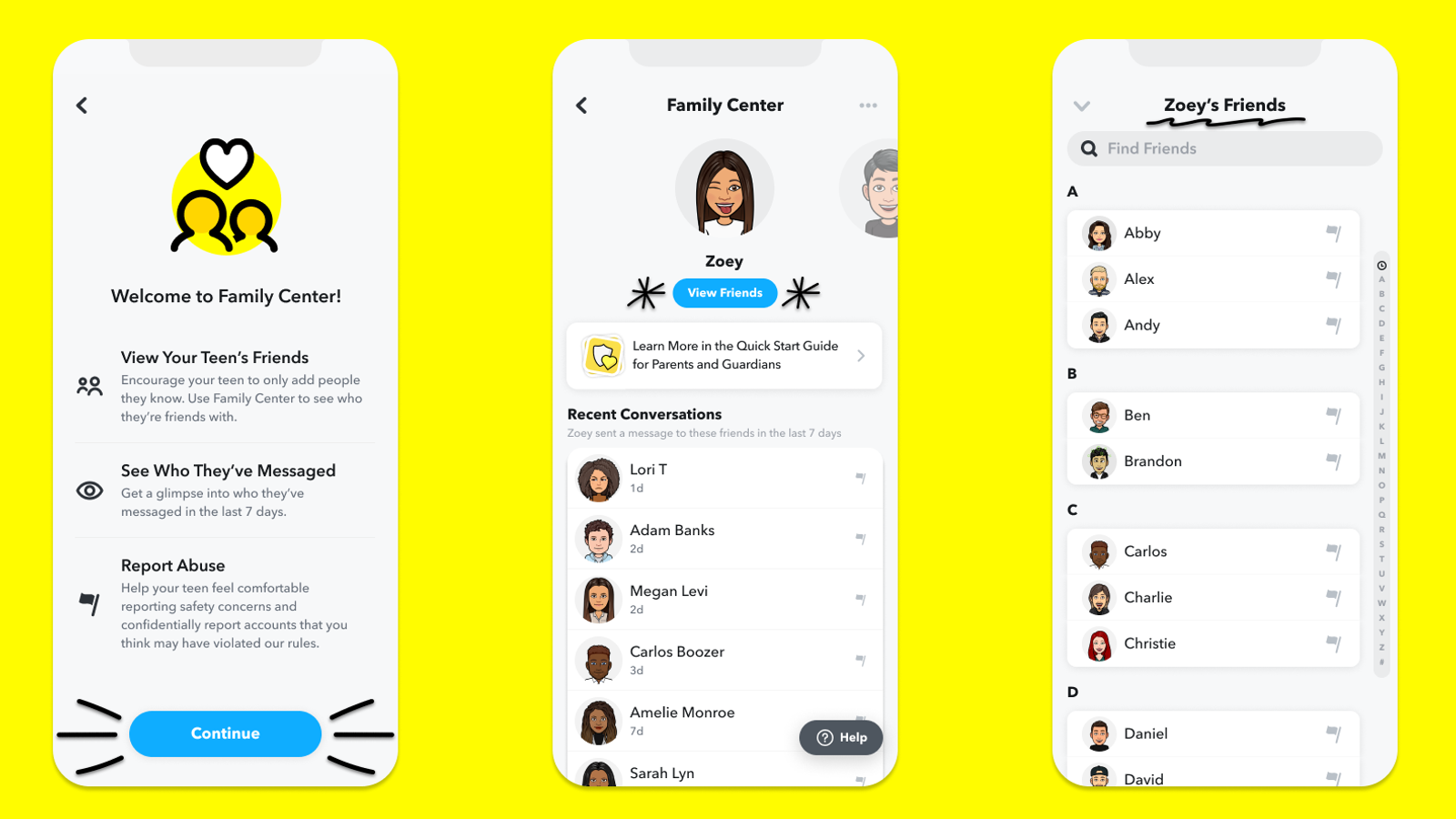

Snapchat is launching a new feature which will give parents some access into their children’s activities on the platform.

It requires the child’s account to agree to link up with an account belonging to someone over 25, but the Family Center tool will show parents their child’s friends list and when they last spoke to each friend within the last week.

The tool will not reveal the actual conversations, explained Snapchat‘s head of global platform safety Jacqueline Beauchere, who told Sky News the point is “insight” rather than “oversight”.

The idea is to reflect “the way that parents engage with their teens in the real world, where parents usually know who their teens are friends with and when they are hanging out – but don’t eavesdrop on their private conversations”.

“Family Centre is about sparking meaningful, constructive conversations between parents and teens about staying safe online,” added Ms Beauchere.

“We hope that these features empower both parents and teens, by offering parents those critical insights into who their teens are connecting with on Snapchat, and at the same time safeguarding teens’ needs for privacy and their growing independence.”

The company said the product was informed by a study it did with more than 9,000 teens across several platforms which found that parents and teens who were in regular conversation about the child’s online activities were more likely to be trusting and to share information when they came across online risks.

Teenager jailed after hacking into Snapchat accounts and demanding money from victims’ friends

Snapchat launched on web – allowing users to log on without mobile phone

Semina Halliwell: Rape victim, 12, took her own life directly after police interview, her mother tells Sky News

Read more: Snapchat admits age verification failures to MPs

It is launched as the UK continues to develop its Online Safety Bill, a controversial law which aims to protect children online by obliging social media firms to tackle harmful content even if it isn’t illegal.

There are numerous extreme examples of illegal content causing harm on Snapchat too, including the grooming of Semina Halliwell, a 12-year-old girl who took her own life, the intimidation of rape and sex trafficking victims in Hull, and the case of Gemma Watts, a 21-year-old woman who posed as a teenage boy on Snapchat and Instagram to meet and sexually assault young girls.

In all of these cases potential evidence was not sought from Snapchat because of one of the platform’s key features – disappearing messages – which meant the Snaps or Chats featuring the grooming or threats were not recoverable by the company.

Snapchat does have the ability to keep these messages, but it doesn’t do so unless it receives a user report flagging the communication as warranting an investigation.

Ms Beauchere acknowledged to Sky News that the company relies “so heavily on reporting from our community”.

Reluctance to report accounts

This dependence is not unique to Snapchat. There is an ongoing and sector-wide debate about how social media platforms should moderate the enormous volumes of content being shared on them by millions of people.

For Snapchat, the moderation challenge is only true of direct messages – all content that is broadcast publicly is checked before it can go live – but the expectation of privacy also obliges the company to constrain what content moderators are able to pre-emptively check.

To address this Snapchat tries to encourage reports from its teenager user base, and through the Family Center will also allow parents to “easily and confidentially report any accounts that may be concerning” to the company’s safety team.

“We’ve known from research that young people are disinclined to report for a variety of reasons.

“Some of them might be rooted in social dynamics, others might rest with perceptions about the platform and what the platform will or will not do,” said Ms Beauchere.

The company’s research into this found a significant number of teens feared being judged for reporting content, or felt pressure not to make a report when someone that they knew personally behaved badly.

“Is it the very nature of the term ‘reporting’ that’s the problem, because they think of reporting as snitching or tattletaling? We’re trying to encourage them that that’s not the case,” Ms Beauchere said.

“We have teams in place 24/7 ready to respond to these reports, but we need to see that engagement from our community,” she added.