Despite their best efforts, European countries’ governments have so far been unable to curb inflation this year. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the spark that finally triggered the crisis that loomed since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

In June, EU member states released their consumer price index (CPI), showing that prices have risen significantly from the numbers released in June. Spain recorded a 10.8% increase in CPI, with Belgium close behind its 10.4% increase. Austria and Portugal saw their CPIs increase by 9.3% and 9.1%, while Germany and Italy saw increases of 8.5% and 8.4%. The CPI in France increased by 6.1% from its June numbers.

To combat the rising inflation, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised its three key interest rates by 50 basis points. The interest rate on the main refinancing options and the interest rates on the marginal lending facility have been increased to 0.50% and 0.75%, making it the first time the ECB has hiked rates since 2011.

Christine Lagarde, the president of the ECB, said that the higher interest rates will put downward pressure on prices and help ECB drop inflation to 2%. However, Lagarde’s plan will only work “in the absence of new disruptions,” with energy costs stabilizing and supply bottlenecks easing.

So far, the rapidly dropping real rates spell only trouble for the Eurozone. With the winter approaching fast, energy prices are starting to increase significantly in the EU, with some countries actively planning for intermittent blackouts throughout the fall and winter.

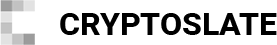

In Germany and France, the year-ahead prices per megawatt hour have increased 10x since last year, with other countries preparing for increases that could exceed 1,000% by the end of the winter.

Economists have warned that the energy shortfall could shut down factories and bankrupt small businesses unable to bear the cost of electricity.

Although many believe that the end of the war in Ukraine will end Europe’s energy crisis, there are multiple other factors at play that could extend the crisis way past the war.

Europe’s reliance on Russian natural gas has shut down nuclear power production in the region. This reduction in nuclear energy usage hit France the hardest, as 31 of its 57 nuclear reactors are down due to emergency maintenance. Since the beginning of the year, France has imported energy for a record 102 days. In comparison, the country imported no energy between 2014 and 2016.

The EU’s push for green energy has also caused many countries to deactivate their coal-fired power plants and switch to natural gas or renewable energy sources like solar or wind. This was felt the most in Germany, where the local government’s efforts to decrease the reliance on polluting energy sources could backfire. With few other countries as dependent on Russian gas as Germany, the country is now left to deal with the blowback from rising energy prices and their effects on the economy.

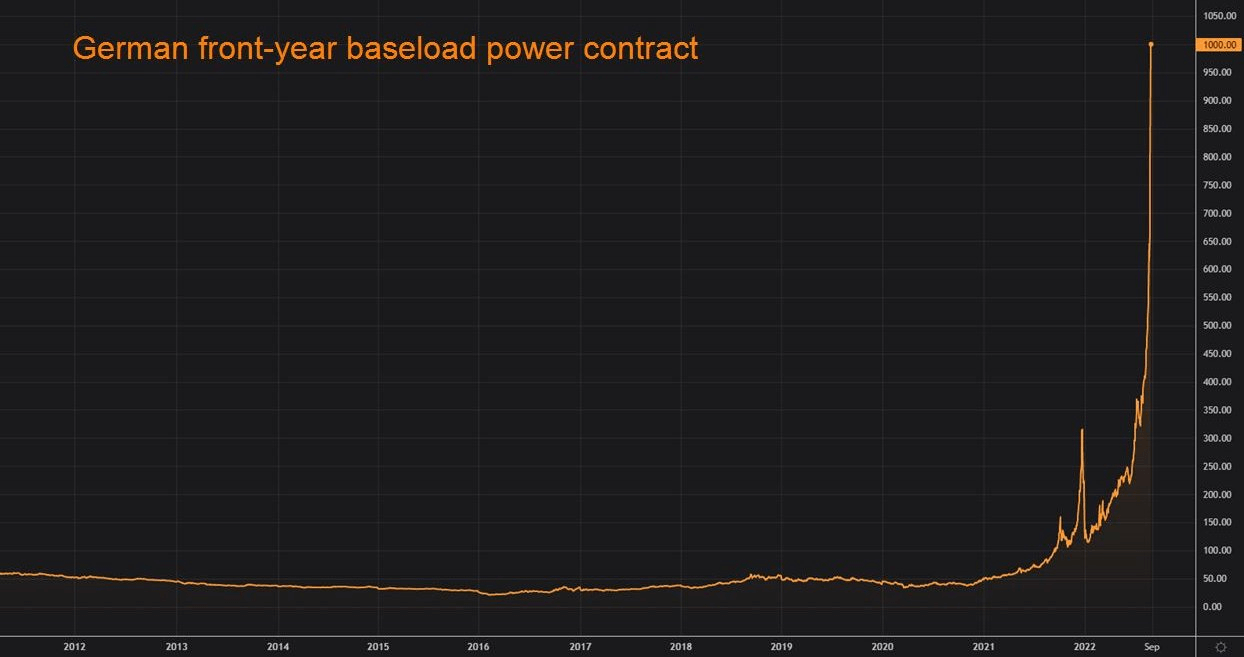

Germany’s producer price index (PPI) increased by 33% in July and is expected to rise as winter approaches. Every increase in PPI affects producers and consumers — rising production costs make local manufacturers less competitive and destroy their margins. In contrast, consumers bear the rising cost of the final product. Continually growing PPI and CPI even led German labor unions to call for a state-wide 8% wage hike, a move many economists warned could further exacerbate inflation.

In the meantime, ECB’s attempts to fight inflation in its southern member states have resulted in even more damage to the euro.

In July, the ECB revealed its new plan to cap borrowing costs in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece by buying the countries’ state bonds if their debt yields rise too far. Data released earlier this month revealed that the ECB deployed 17.3 billion euros to purchase bonds from the EU’s southern members. The debt was bought using the funds from maturing debt in its existing bond holdings. Official statistics show that the ECB’s net holdings in German, French, and Dutch bonds dropped by 18.9 billion euros in the past two months.

To facilitate its aggressive bond buying, the ECB divided the EU into three categories — donors comprising Germany, France, and the Netherlands, and recipients comprising Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, and neutrals.

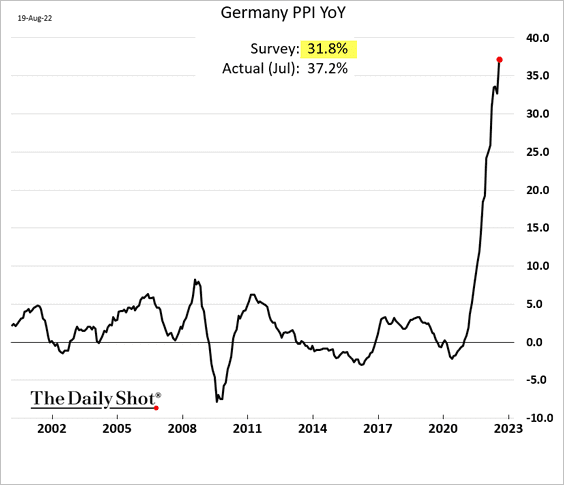

The bank said that the financial fragmentation between these categories forced it to activate these purchases. When the ECB announced the plan, the BTP-Bund spread hit a two-year high of 250 basis points.

The BTP-Bund spread is the difference between the yield on 10-year Italian government bonds (BTPs) and German 10-year bonds (bunds). The bond purchase managed to decrease this difference to 183 basis points, but it rose back to 229 points in a month as political instability in Italy put the country’s economic stability into question.

The importance of the BTP-Bund spread lies in Germany’s position. German debt has historically been considered a risk-free benchmark to which all EU debt was compared. However, the soaring inflation and looming energy deficit expected in the winter have the potential to shake up Germany’s ranking as a risk-free benchmark for sovereign debt in Europe and introduce more volatility into the secondary bond market.

Many banks and institutions are questioning both the effectiveness and the legality of the ECB’s intervention in Italy. Aggressive bond purchases shut down any attempts to stabilize inflation in the country.

Meanwhile, rising bond yields could cause EU members to default and enter into hyperinflation. With all members of the EU sharing the same currency, a hyperinflated euro in one member state could cause the rest to experience similar volatility.

This makes the ECB the buyer of last resort for the majority of the European bond market, as the central bank will fight to prevent its members from defaulting. The ECB will need to print more money to fund these bond purchases if the debt in its existing bond holdings doesn’t mature in time. However, increasing the rate of printing new euros will do little to curb the rising inflation in Europe.

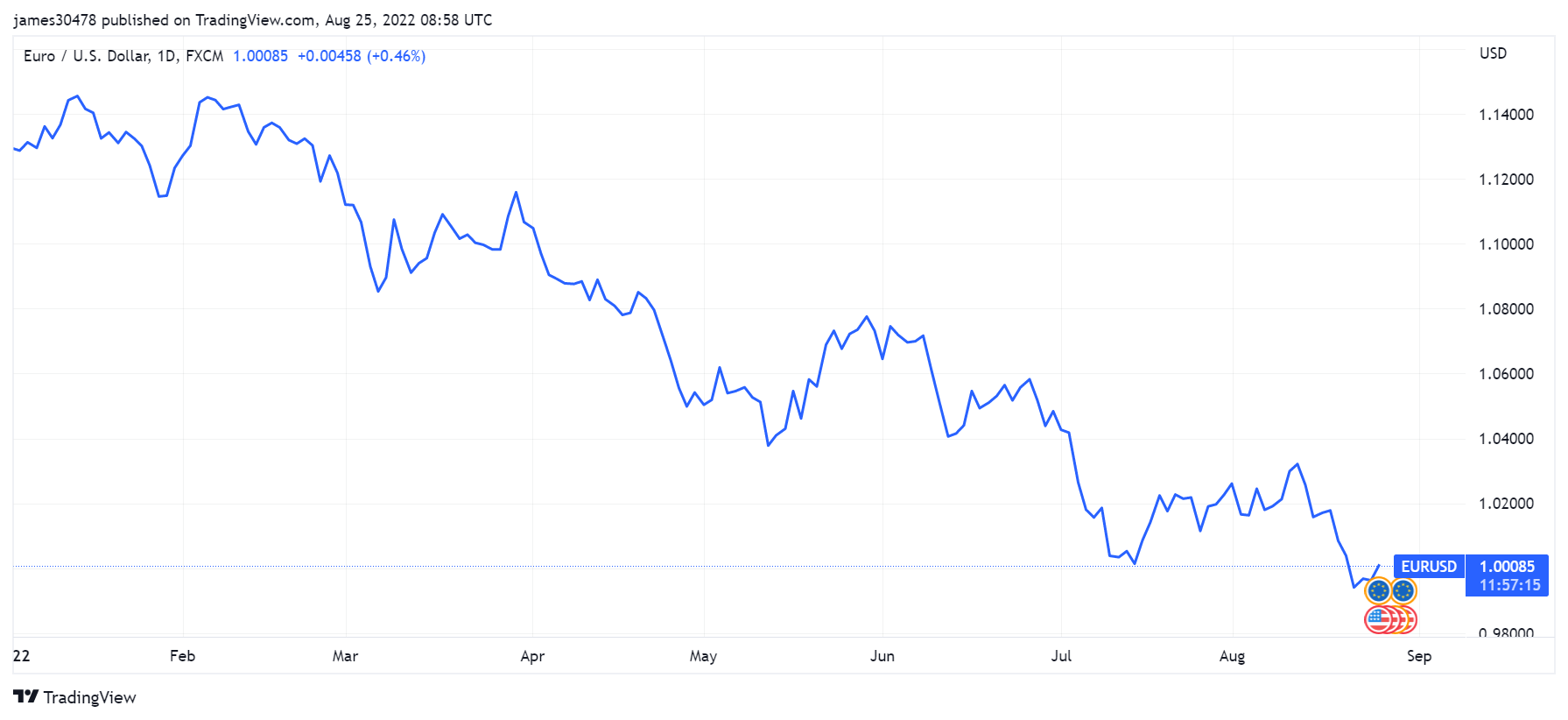

The second-largest currency in the world by market cap, the euro has lost 16% of its value against the US dollar since the beginning of the year. It has also fallen below parity against the US dollar for the second time this year.

If the Federal Reserve keeps raising rates and the ECB continues to buy Europe’s debt, this downward trend could continue in the months to come and further exacerbate rising energy and food prices.

Historically, people have flocked to hard and scarce assets in times of recession, choosing tangible investments like commodities, land, and real estate. If a recession hits Europe in full force, we could see an influx of money into the crypto market, especially Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s reputation as a safe-haven asset could make it attractive both as a long-term investment and as a store of value. Recent efforts from the Russian and Iranian governments to introduce cryptocurrencies as a means of payment could lead to other countries following suit. Increased adoption could eventually lead to large regional gas and energy producers requesting cryptocurrency payments if the euro remains on its current path.

The post Research: The European sovereign debt crisis 2.0 appeared first on CryptoSlate.