This article was supposed to be a considered look at whether or not this mini-budget will generate the growth it was promising.

It was supposed to be about whether it made sense to borrow so much money to finance tax cuts and whether this economic gamble (for a gamble it is) will actually work out.

And in one respect it is still about all those things, but in most respects it is about the extraordinary response from financial markets.

I cannot remember another fiscal event which has prompted a reaction like this: the pound down very sharply; gilt yields (the government’s cost of borrowing) up more than any other day in modern records; stock markets down and money markets pointing towards a painful rise in Bank of England interest rates in the coming months.

It’s possible to dismiss all of this as the moaning of the men in grey suits, except that this matters.

Think about it for a moment: the UK government has just committed to borrowing stupendous sums to finance a swathe of tax cuts. It has done so in the hope that this will generate extra growth, shifting Britain’s disappointing productivity trajectory on to a new level.

There is some logic to this, and we can debate whether today’s mini-budget had the right kinds of reforms, but what matters even more than any of that is being able to borrow all that money, which in turn comes back to those international capital markets.

The mini-budget – did the rich just get richer?

Tax change calculator: see how much you will save

Mini-budget: The key announcements from the chancellor at a glance

And the message from those capital markets is not encouraging. The reason government bond yields are up so sharply is because investors think we are a riskier proposition than we were in the morning. They want to charge us higher interest rates in the same way any lender does with a heavily indebted borrower.

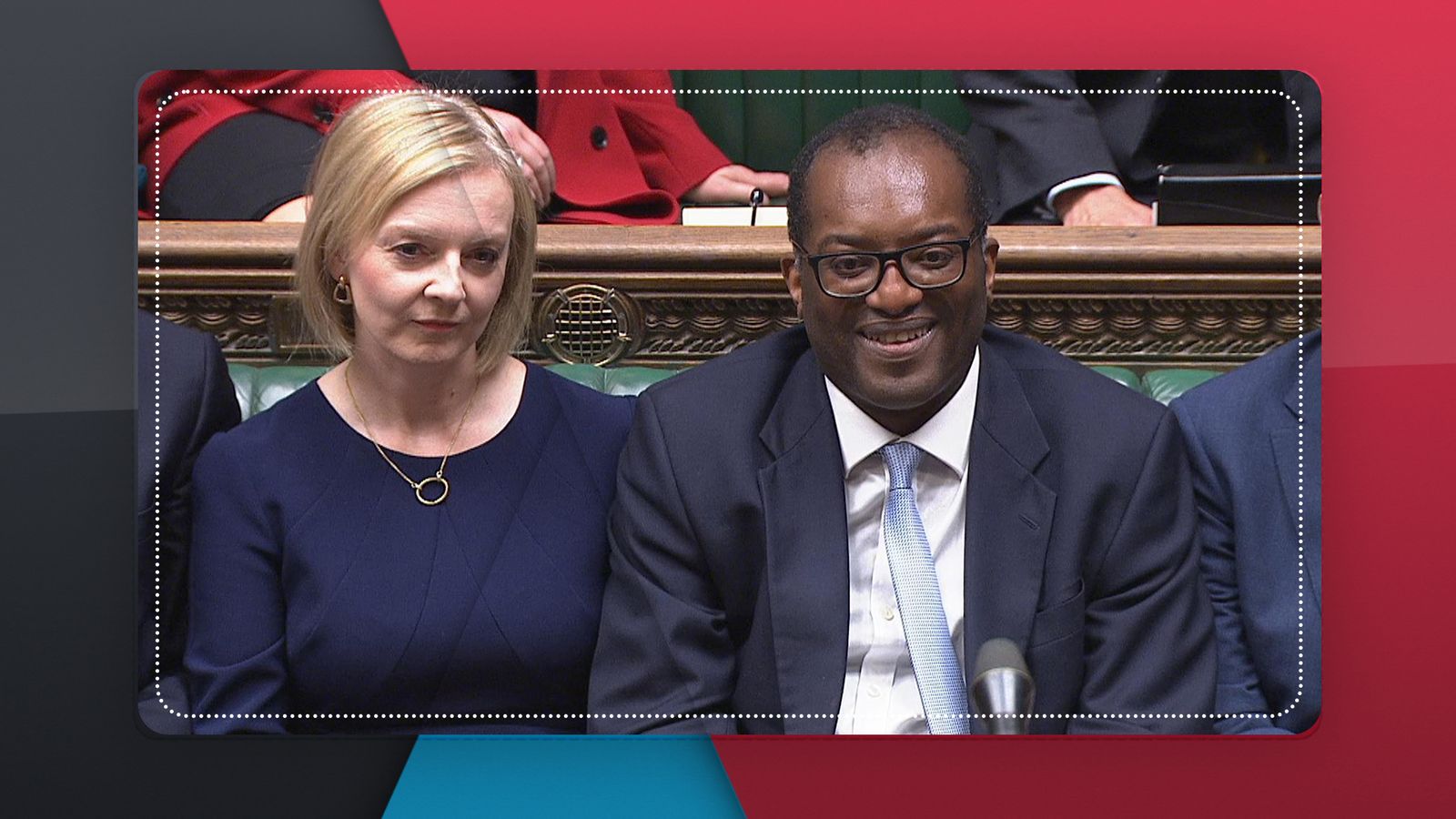

But the direct upshot of that is that in the hours after Kwasi Kwarteng sat down, these hundreds of billions of pounds worth of borrowed money instantly became much more expensive.

The fall in the pound is perhaps more worrying. Don’t get me wrong: we have had plenty of tough days for sterling before, and this is nothing in comparison with the night of the EU Referendum.

We survived that – albeit that the pound never recovered – so why won’t we shake this off?

And indeed, in the coming days sterling may well rally and things will look a little less depressing.

Even so, consider what these currency movements signify: this is a lot of investors pulling their money out of this country, deciding not to allocate cash to the UK, drawing back rather than diving in.

If those investors were excited about Britain’s growth plan you’d expect them to want to be a part of it; you’d expect them to begin allocating cash to UK investments; instead the opposite seems to be happening.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

The verdict, in short, is not especially encouraging. No other budget in modern times has seen a reaction quite like this. Perhaps the closest analogy is the budget this one has already been compared to: Anthony Barber’s 1972 budget.

That was another attempt to boost economic growth a few years ahead of an election; it ended badly, with a monetary and fiscal crunch, and inflation soaring to double digits.

Now, in some respects the territory is very different today to the 1970s. For one thing, the pound is happily floating while in the early 1970s it was juddering around at the end of the Bretton Woods era.

Indeed, you could make the case that today’s fall in sterling is a mark of success: when times change, our currency adjusts to it. And another difference is that the Treasury no longer decides interest rates; those get set on the other side of town by the independent Bank of England.

But here, again, things get uncomfortable. The bank is duty bound to try to ensure financial stability. It is the guardian of the pound.

If sterling carries on falling it is not beyond the realm of possibilities that the bank steps in with an interest rate increase. Some economists think this could happen as soon as next week; indeed, that’s pretty much priced in by money markets.

Those markets are betting on interest rates getting up to 5.5% next year. That’s almost a percentage point higher than they were expecting before Mr Kwarteng stood up.

Interest rates of those levels would be higher – once you adjust for people’s mortgage indebtedness – than anything we saw since the late 1980s, when the housing market was heading for the biggest crash in modern times.

This is not a happy precedent, yet it is what markets are now betting on.

The next days could be bumpy. The hope is that the pound rallies in the coming weeks, but there is also a chance that it continues to drop. This is not yet a crisis. But it doesn’t look especially good.