Every year, just 18 oil and gas platforms in the North Sea, licensed by the UK government, are losing enough gas to power 140,000 homes.

That is the equivalent of a city the size of Aberdeen.

This is the conclusion of new analysis of a practice generating pollution in our own backyard – that suggests how it could be fixed – which has been shared exclusively with Sky News.

“It’s a huge waste of gas, basically,” said Liam Hardy from think tank Green Alliance, which conducted the research.

“Especially in the middle of a cost of living crisis, it’s particularly upsetting and disappointing that we’re wasting that gas, and we’re polluting the atmosphere at the same time.”

Green Alliance says this “waste” can be stopped by 2025 by bringing forward a ban on practices known as venting and flaring.

The government says that’s not possible. The industry says it already has a plan.

What is venting and flaring, and why is it bad?

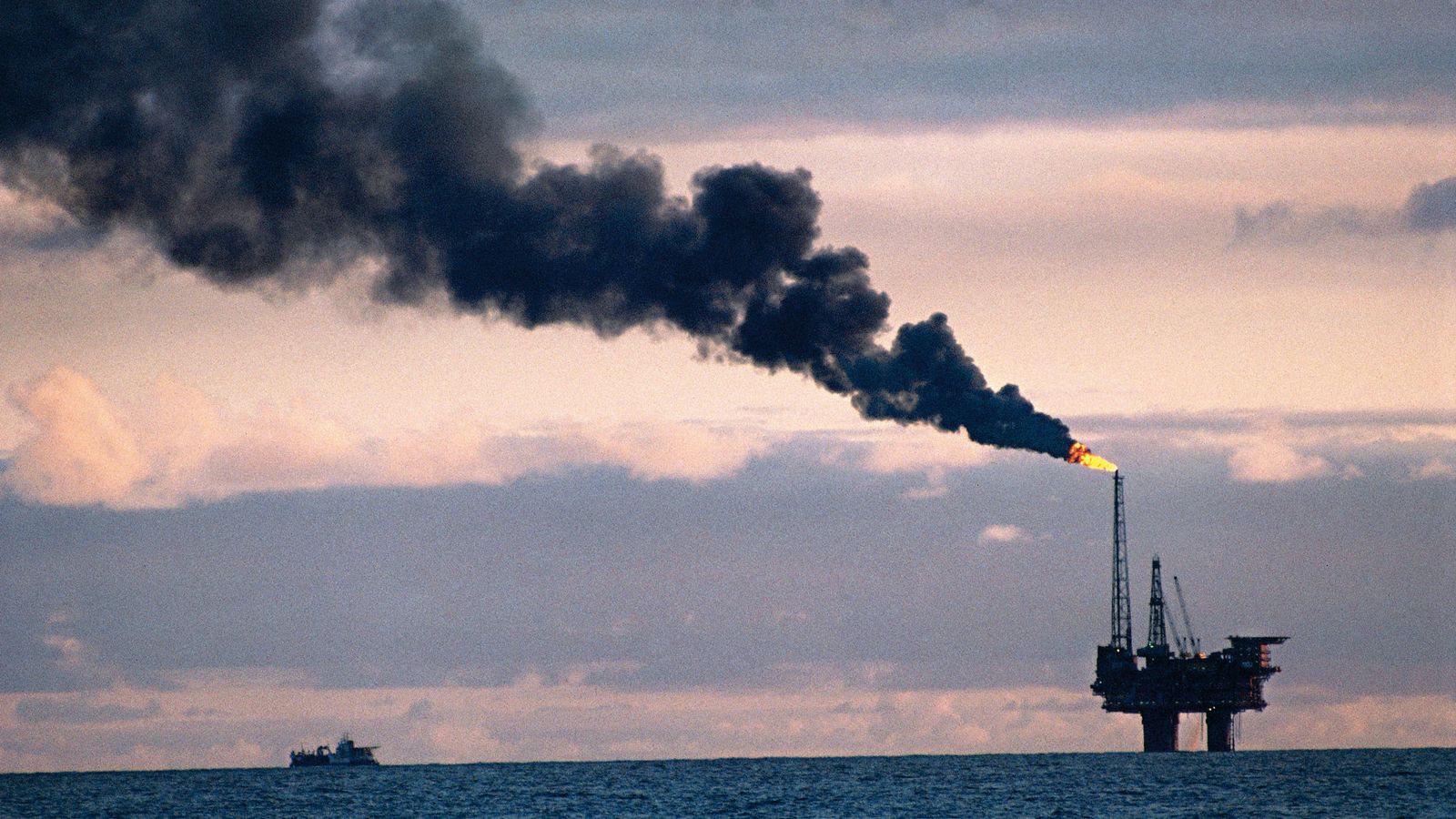

Venting and flaring happens when oil or gas field operators have extra gas they need to get rid of.

For example, when gas comes up with oil in a platform only designed to capture the oil, or if the gas is too dirty.

The operator either releases the gas as methane directly into the atmosphere, known as venting, or burns it, which is called flaring.

Flaring releases substantial volumes of potent greenhouse gases, including black soot and nitrous oxide.

Venting is even worse for the environment because it releases more methane, a gas that warms the atmosphere at least 30 times more than carbon dioxide.

It is happening all around the world.

That’s why methane is one of the key issues on the negotiating table at the COP28 climate talks, kicking off in Dubai next week.

A lot of this methane is the same as that burning in our boilers, and so should be captured and used to heat homes, Green Alliance said.

The International Energy Agency calls it an “extraordinary waste of money” because companies could sell the gas.

How bad is venting and flaring in UK territory?

There are currently 284 UK-licenced offshore fields in production in the North Sea, according to the regulator, the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA).

The think tank has identified the 40 worst offending for venting and flaring.

Green Alliance estimates that venting alone accounts for around 2.5% of UK methane emissions.

What can be done?

The government is banning venting and flaring from 2030 – there will be exceptions for emergencies.

Green Alliance says that can be brought forward to 2025, as did the net-zero review earlier this year, and the government’s climate advisers, the CCC.

Doing so would mean those sites that are producing “negligible” oil or gas but releasing a lot of methane, and are due to shut soon anyway (14 sites shown in red in the map above) would close in 2025 instead.

The gas lost from these sites would be offset by that captured from just 18 of the top 40 sites (in orange) that will likely be producing for some time, so should have the technology added to capture the gas sooner, Green Alliance says.

This is what would prevent 5.2 billion cubic feet of gas being released into the air every year – and supply 140,000 homes with energy. These figures could rise if applied to all sites, not just those in the top 40.

“We can actually grow the UK’s domestic production of gas by ending routine venting and flaring,” Green Alliance said.

Other sites, such as those that are producing a lot of oil and gas still but are due to close soon (shown in yellow), could qualify for an exemption.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Click to subscribe to ClimateCast wherever you get your podcasts

Is a 2025 ban realistic?

Grant Allen, professor of atmospheric physics at Manchester University, said: “Reducing emissions from flaring and venting is one of the potential climate quick wins.

“With good monitoring, industrial practice, and only small changes in industrial technology, it is possible to greatly reduce unnecessary emissions from flaring and venting.”

The International Energy Agency has said various technology exists to capture and potentially sell the gas instead.

In some cases it will cost, requiring extra support or legislation from governments, in others it can make money.

Professor Stuart Haszeldine from Edinburgh University said the government may have to tweak some financial levers to make the changes more economical for operators.

But “[retrofitting] those installations would be difficult within the timeframe that we’re looking at”, said Mark Wilson from industry body Offshore Energies UK. It could also mean having to turn sites off.

Read more:

London factory to reduce waste by renewing 30,000 garments a year

Former Sky News boss says he ‘failed’ on climate change coverage

Mr Wilson said every site already had a “robust” plan to reduce all emissions, and had already cut methane emissions by 45% and flaring by 11%.

“We’ve already made huge strides to reduce emissions… We’ve done that because we’re doing it in a programmed, well-thought-out way,” he added.

A Department for Energy Security and Net Zero spokesperson said the UK adopted “early and ambitious measures to tackle methane emissions”, leading to significant falls already.

“We do recognise the urgency to go further, which is why we are committed to banning routine venting and flaring by 2030.”

They said accelerating the targets would “lead to an early end of production” from some sites and further reliance on imported gas with higher emissions.

Green Alliance said the lost gas would be more than compensated for by that captured from the sites that have technology fitted early.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

The UK is off track on a global goal on methane that the country itself engineered.

At the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in 2021, the UK government announced the Global Methane Pledge, under which around 100 countries agreed to slash dangerous methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

Green Alliance analysis suggests the UK is on course for 19%.

Norway and Denmark have banned routine flaring.

Last week, the European Union committed to a ban from 2027 and a possible penalty on imports.

Lisa Fischer from green energy think tank E3G said the UK is “lagging behind”.