Satellite images that can monitor the earth and measure climate risks such as flooding, famine, forest fires and detect hazardous pollutants in air and water can be invaluable to scientists, governments, and industry.

This is exactly the data that Bengaluru based Pixxel Space provides to its clients.

Its hyperspectral satellite cameras can detect invisible gas leaks, crop diseases and infestations, health of crops and soil, underground oil leaks, or the moisture content in a forest that could potentially light up.

Awais Ahmed, 26, founder and chief executive, tells Sky News: “Human eyes can see things in the red, green and blue which is in the visible range.

“What hyperspectral cameras do is they take this light, in the visible and the infrared range, split them into hundreds of very minute wavelengths that are continuous in nature.

“That splitting will tell you exactly what species of crop is growing or what gases are being leaked, and you know whether it’s an underground oil leakage or something else.”

Climate change and environment is at the heart of its operations, which has made it one of the most sought-after companies.

‘We can be killed in the UK at any time’: Sikh activist fears for life after being named on Indian ‘hit list’

India: Tear gas dropped from drones as protesting farmers march towards New Delhi

Jagtar Singh Johal: Brother of imprisoned Briton tells Lord Cameron ‘his life is in your hands’

It has more than 80 customers and collaborated with the US government’s National Reconnaissance Office, EUSI, and Japan Space Imaging.

It has also cooperated with leading American, British, and European private companies on projects.

It clinched a deal worth £28.5m with Google’s Alphabet on its constellation project and since 2020 raised £57m.

With offices in America and India, the company is barely four years old with 180 employees, most under the age of 28.

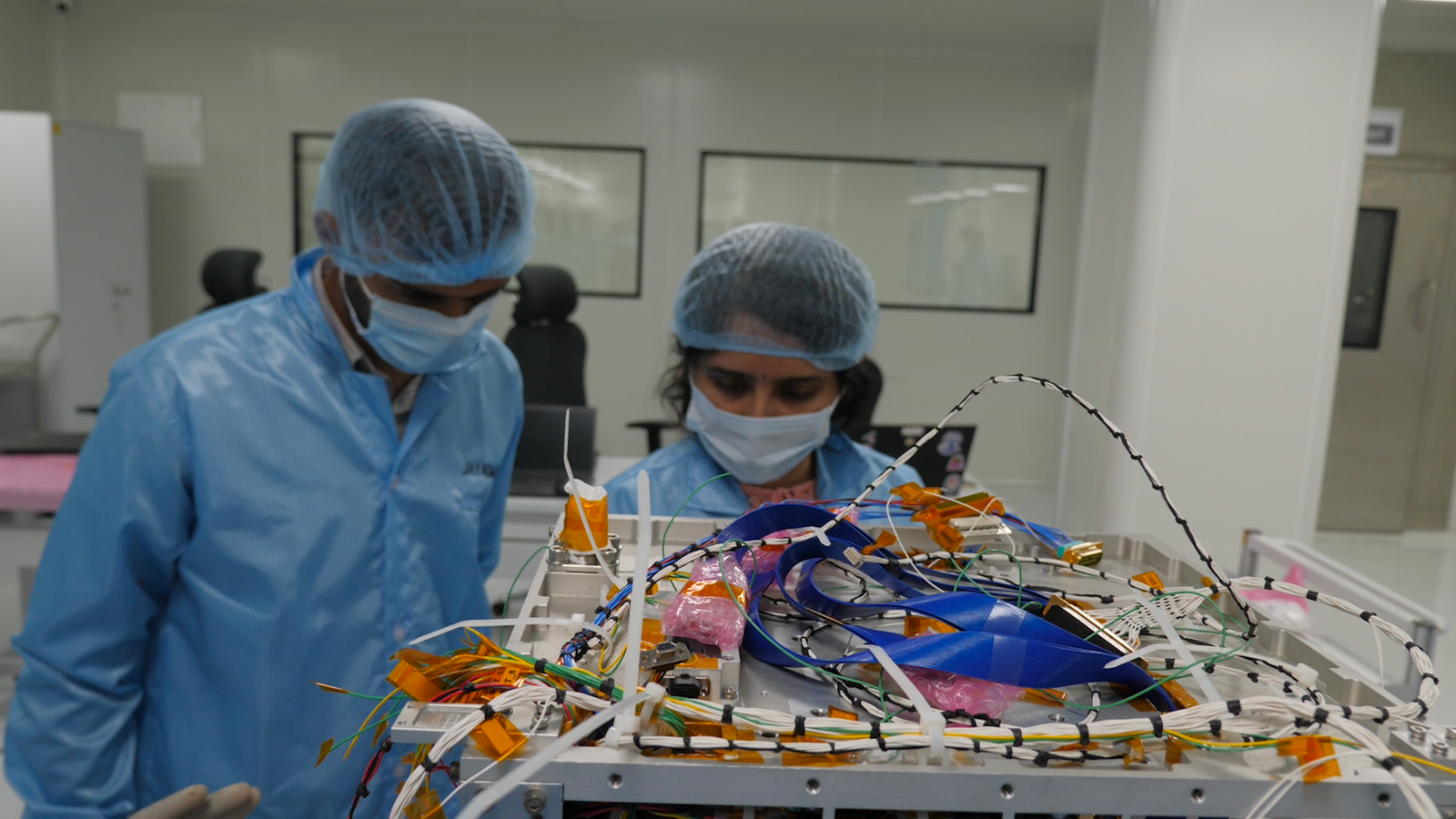

In the company’s sanitised and dust-free “Clean Room” engineers feverishly assemble the next satellite to be launched in the summer.

The plan is to launch six more satellites by the end of this year and have a constellation of nine, monitoring the health of the planet every 24 hours.

Mr Ahmed says: “The more data points that we are able to capture, the better the analytical planetary models become which help us predict certain things.

“If we can capture the parameters of the potential yield of a crop, then we can plan for it from a food security standpoint.

“If we know the moisture levels of a forest is low, we can help provide advanced warning of emergency and disaster response to forest fires.”

“Even industries that you would think are responsible for creating the damage, like oil and gas companies, are working with our satellite data to see how the leaks will impact the environment or mining operations that might end up creating havoc in the ecological sphere.”

A booming space industry

Since the Indian government opened the space sector to private enterprise in June 2020, there has been a boom in the industry.

There are almost 400 companies and close to 200 start-ups that have mushroomed across the country.

In 2022 the global space economy was worth £432bn while India accounted for less than 2% of that market. It is now one of the fastest-growing and most sought-after segments with explosive scope and potential.

Foreign investment has seen a 20-fold growth, from $6m (£4.7m) in 2019 to $125m (£99m) in 2023.

The successful landing of a craft on the south side of the moon, the first by any country surely turned a spotlight on its space capabilities and programs.

Read more:

SpaceX rocket launches for moon’s mysterious south pole

India PM inaugurates controversial temple

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Since it launched its first rocket in 1963, the country’s space segment has been largely under the purview of the government-run Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

Though it still has an overbearing arch on the sector, private companies are making rapid inroads into gaps and opportunities in many avenues.

Cutting-edge technology, leveraging the unique low-cost structure, and a large talent pool available – as the country churns out 1.5 million engineers every year – has fuelled the new space economy.

From manufacturing rockets and satellites, launching them, operating earth stations, and disseminating satellite data to developing downstream space applications, private companies will be potential game changers in this industry.

Provided they are assisted with more stimulus and support by the government, and at a galactic pace.