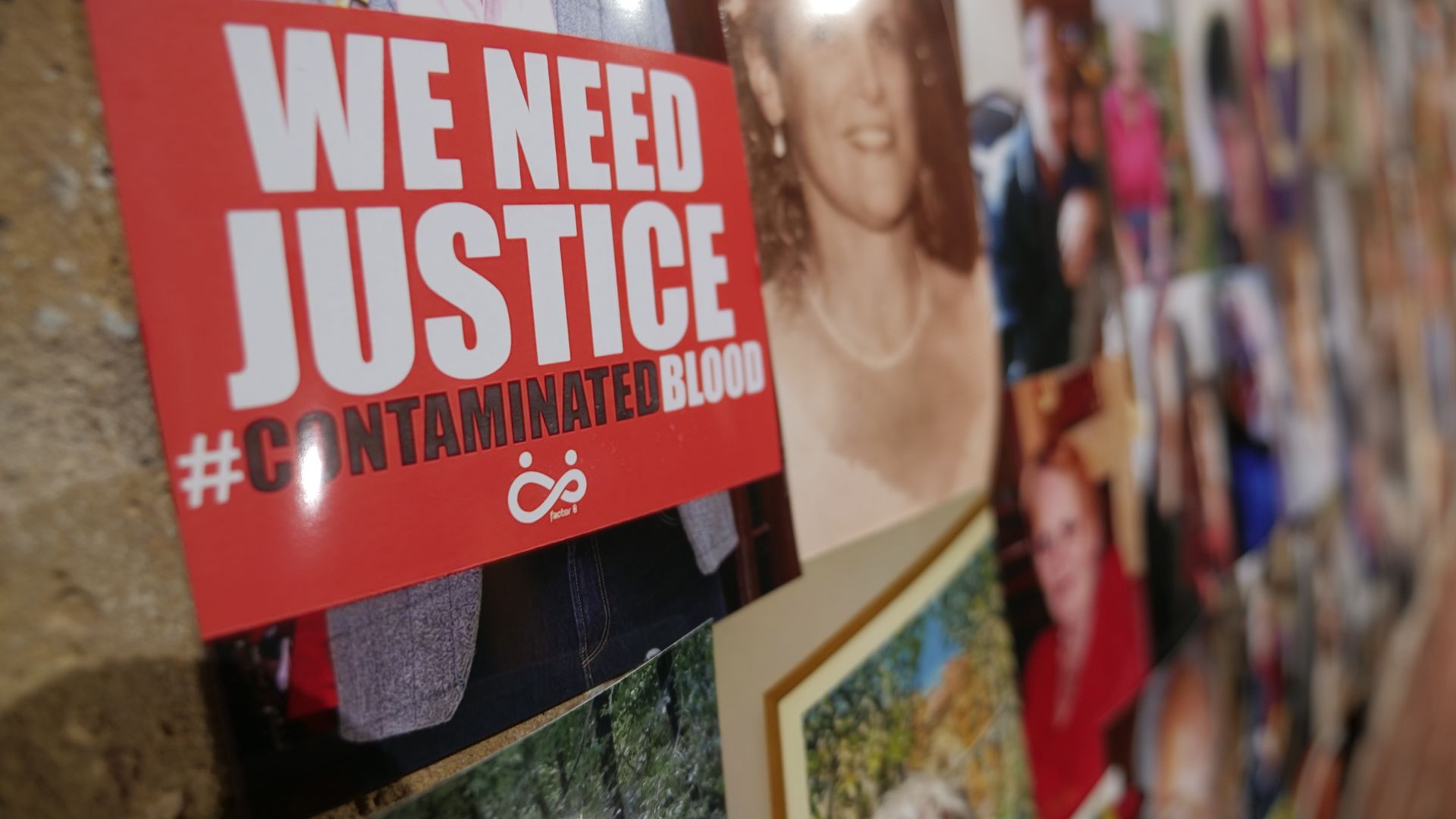

It has taken decades, the loss of thousands of lives and an exhausting battle to have their harrowing, heartbreaking stories heard.

Now the end is almost in sight. In just over three weeks, Sir Brian Langstaff will deliver his long-awaited report into the infected blood scandal.

But for those who have suffered so much, there is still so much to fear.

Jason Evans lost his father to AIDS when he was just four years old after Jonathan Evans’s NHS treatment for haemophilia included blood products contaminated with HIV.

Mr Evans said: “My first memory is being at his parents’ house on my fourth birthday, and he was dying of AIDS in a bed.

“In the 70s, he began to be given the new Factor VIII (8) product, which infected him with hepatitis C and then into the 80s he was also infected with HIV.”

Mr Evans has devoted his life to uncovering the truth behind the scandal by searching for evidence of serious failures by successive governments to address the greatest treatment scandal in NHS history.

Rishi Sunak says government ‘speeding up’ compensation for infected blood victims

Infected blood inquiry chair ‘sorry’ as final report on scandal delayed again

Sunak suffers first Commons defeat as MPs vote for infected blood compensation body

He has found documents that prove unethical trials involving children were taking place, without their parents’ knowledge when clinicians were already aware of the risks using unscreened blood products.

His discoveries support claims of decades of cover-ups and a conspiracy of silence to prevent the full truth being known. The unethical trials went on nationwide.

Mr Evans said: “My own father was infected as part of a trial which was run by the Public Health Laboratory Service. It actually says so in his records. Knowing and accepting all of that is difficult. The government has never accepted responsibility for it.”

Sky News has also seen documents that show Margaret Thatcher rejected calls for a special inquiry into the scandal as early as June 1990 and was against paying further compensation.

One of them is a letter from the then prime minister to D G Watters, Secretary General of The Haemophilia Society, who had written to her suggesting a special inquiry on 28 June 1990.

She replied: “In the present case, the government has not accepted that the infection of haemophiliacs with the AIDS virus – tragic as it is – was the result of negligence; or that we should depart from the view reached by the Pearson Committee when it rejected the arguments for some general scheme of no-fault compensation.

“I am, therefore, not clear precisely what question you envisage a special enquiry would be asked to examine. If an enquiry were to attempt to establish whether there had been any negligence, either in general or for particular categories of claimants, it would need to sift through exactly the same kind of evidence as the present legal action.”

It is this dogged refusal to accept any wrongdoing and award compensation by successive governments that worries Stuart McClean.

He was just eight years old when his mother took him to their doctor after a fall resulted in a swollen knee.

But after being misdiagnosed with haemophilia, Mr McClean was treated with contaminated Factor VIII. This is when he was infected with the potentially deadly hepatitis C virus, something he only discovered as an adult.

On Wednesday, Mr McClean will be among the first of the infected and affected community invited to meet Paymaster General John Glen, the minister responsible for the government’s response to the scandal and the recommendations of the public inquiry.

There are concerns among campaigners that the government may seek to delay paying compensation.

Read more:

Constance Marten and Mark Gordon jury begins deliberations

Woman finds 50,000 bees behind walls in toddler’s bedroom

Mr McClean told Sky News: “This government could have put an end to this a long time ago. This could have been done decades ago, but they’ve dragged it out.

“They’ve been forced kicking and screaming to give us justice and our hope, among all hopes that they will give us justice in the not too distant future.”

On 20 May, thousands of the infected and affected, all victims of the infected blood scandal, will gather at Westminster’s Methodist Hall to hear Sir Brian deliver his final recommendations.

It will be an emotionally-charged event made all the more difficult knowing that 710 members of their community have died since the inquiry began in 2018.

They should be in that hall with them but have not lived to see justice delivered.