The first US moon landing mission in more than 50 years appears to be doomed after a private company’s spacecraft developed a “critical” fuel leak just hours after it launched.

Private firm Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic Technology estimated the Peregrine lander would start losing power in about 40 hours.

The company had managed to orient it towards the sun, so the solar panel could collect sunlight and charge its battery while a team assessed the status of what was termed “a failure in the propulsion system”.

But it soon became clear there was “a critical loss of fuel”, seemingly extinguishing hope for the planned moon landing on 23 February.

It came as it emerged NASA was set to announce delays to its separate moon mission programme.

The problems with the Peregrine Mission-1 lander were reported around seven hours after Monday’s pre-dawn lift-off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

The company said the propulsion system problem “threatens the ability of the spacecraft to soft land on the moon”.

Peregrine Mission 1: Lunar spacecraft suffers ‘critical loss of propellant’

Peregrine: Moon mission carries sports drink and human remains – is this compatible with science?

Peregrine Mission-1: First US spacecraft due to land on moon since the Apollo missions in the 1970s lifts off

The lander is equipped with engines and thrusters for manoeuvring, not only during the cruise to the moon but for lunar descent.

The company said in a statement: “Unfortunately, it appears the failure within the propulsion system is causing a critical loss of propellant.

“The team is working to try and stabilise this loss, but given the situation, we have prioritised maximising the science and data we can capture.

“We are currently assessing what alternative mission profiles may be feasible at this time.”

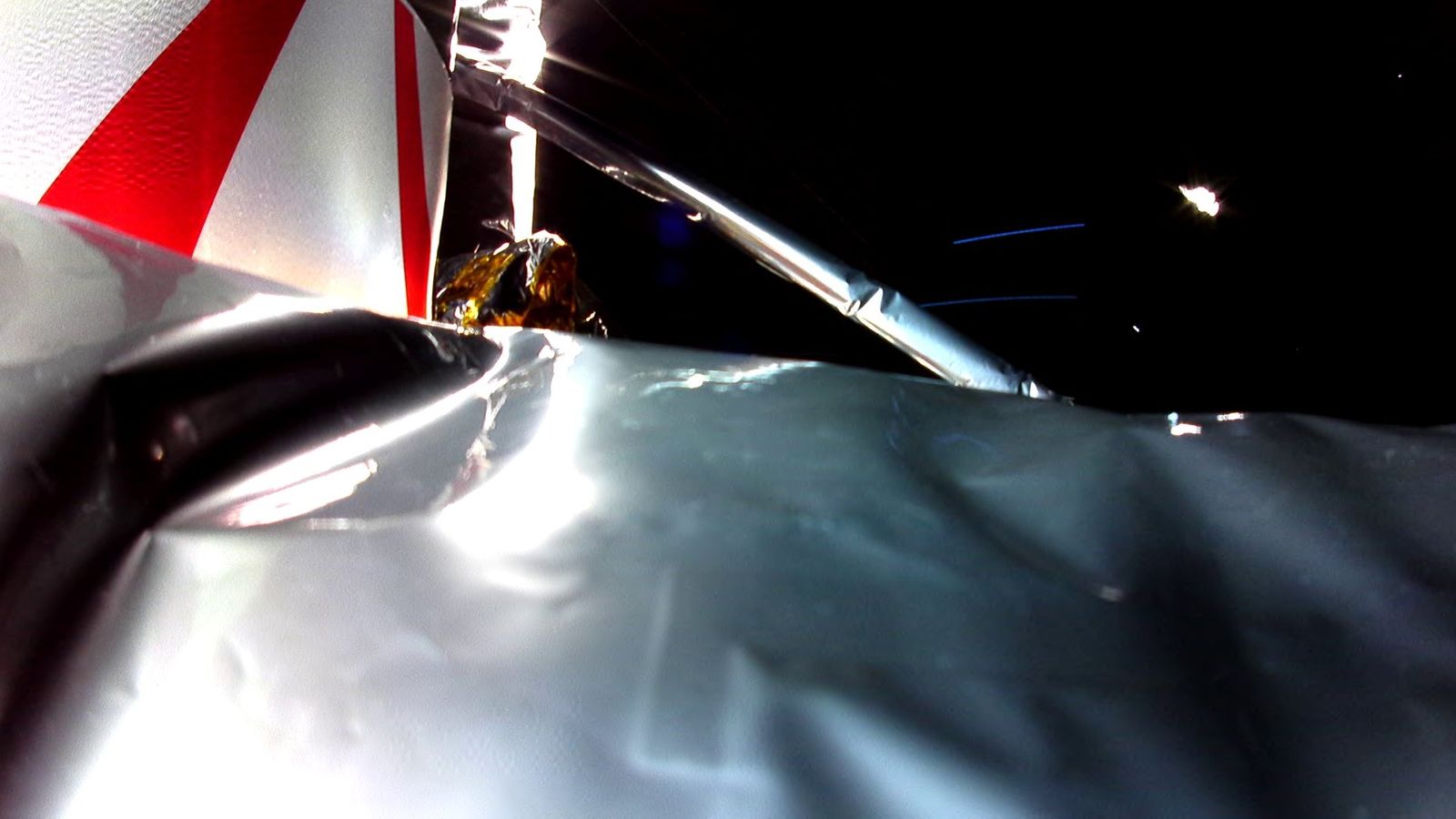

Astrobotic said a photo from a lander-mounted camera, showed a “disturbance” in a section of thermal insulation – which aligned with what was so far known of the problem.

Science correspondent

These are the final hours for the Peregrine mission.

In its latest update, Astrobotic said the spacecraft’s thrusters were working overtime to try and stop it tumbling uncontrollably.

Even if they continued to work well beyond their expected operating life, the fuel would run out after 40 hours or so.

After that, the solar panels could no longer be pointed at the sun and the battery would be used up.

Peregrine has five main engines, used for accelerating and braking, and 12 smaller thrusters for controlling its orientation.

It burns a mixture of hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide, which combust when they are mixed together.

Astrobotic has said the spacecraft has a critical propellant leak.

Even a relatively small escape of fuel in zero gravity would be enough to throw the spacecraft into a slow spin.

That’s why the thrusters are working so hard to keep it stable.

So what now for the spacecraft?

We know that it has left Earth orbit, but Astrobotic hasn’t shared its trajectory.

If it’s on course for the moon it will smash into the surface. More likely it will miss its intended target and head for deep space or be captured by the Sun’s gravity.

But the company is hoping that its systems can be powered up for long enough to get Peregrine to a distance equivalent to its planned journey to the moon.

That would give them a chance to really test the spacecraft in the challenging environment of space, with its vacuum and temperature extremes.

That would give them valuable data for making the next spacecraft more robust.

The company was aiming to be the first private business to successfully land on the moon, something only four countries have accomplished.

A second lander from a Houston company is due to launch next month. NASA gave the two companies millions to build and fly their own lunar landers.

The space agency wants the privately owned landers to scope out the area before astronauts arrive while delivering tech and science experiments for the space agency, other countries and universities.

Astrobotic’s contract with NASA for the Peregrine lander was $108m (£85m) and it has more in the pipeline.

Before the flight, NASA’s Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration, said that while using private companies to make deliveries to the moon would be cheaper and quicker than going the usual government route, there would be added risk.

He stressed that the space agency was willing to accept that risk, saying: “Each success and setback are opportunities to learn and grow.”

Onboard the lander is an instrument known as the Peregrine Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer (PITMS), which was developed in the UK by scientists from The Open University (OU) and the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) RAL Space – the UK’s national space lab – in collaboration with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Washington DC.

The Peregrine lander also contains a number of commercial payloads, including human remains.

They include those of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenbury – with his wife and son – along with icons from the show Nichelle Nichols, James Doohan and DeForest Kelley, who played Nyota Uhura, Montgomery Scott and Dr Leonard McCoy.

The DNA of former US presidents George Washington, Dwight Eisenhower and John F Kennedy are also being transported.

Read more

Why the moon mission matters

Sports drink and human remains – is this moon mission compatible with science?

The last time the US launched a moon-landing mission was in December 1972. Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt became the 11th and 12th men to walk on the moon.

NASA was planning to return astronauts to the moon’s surface within the next few years, but sources say it is set to delay its next few missions under the Artemis programme.

The US space agency was expected to announce changes to the programme on Tuesday, amid mounting technical hurdles with the various spacecraft it intends to use to get to the moon.

NASA has spent months tracking progress with contractors and considering changes to the Artemis programme.

NASA’s second Artemis mission is expected to be pushed beyond its planned late-2024 target after issues were uncovered with the Lockheed Martin-built Orion crew capsule’s batteries during vibration tests, two sources told Reuters.