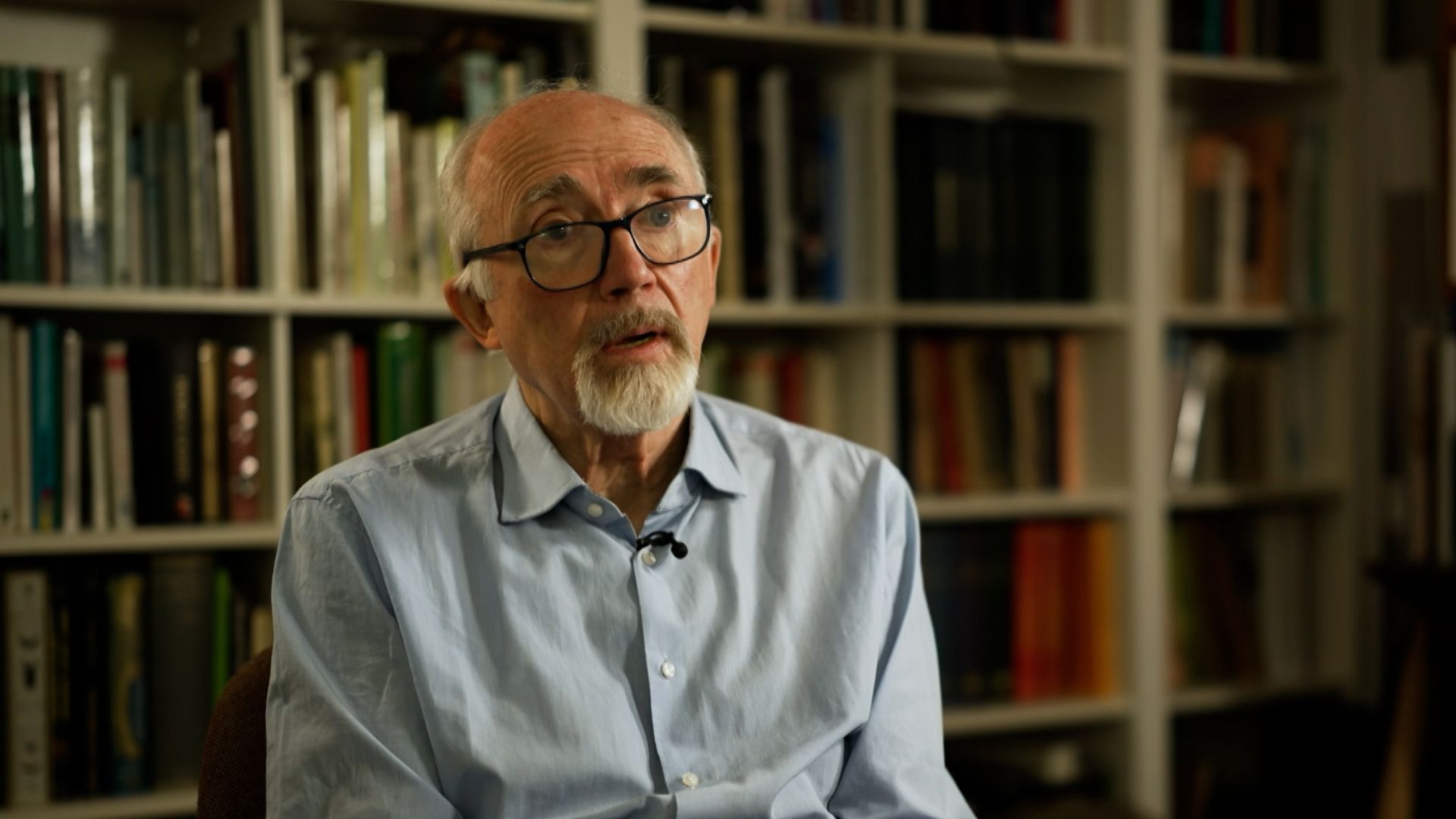

Edward Tuddenham is one of the few remaining haemophilia specialists to have treated patients at the beginning of the infected blood scandal in the early 1970s.

To have infected patients with HIV and Hepatitis C in the course of treating them “is the worst thing you can imagine,” he said.

Prof Tuddenham went on to be one of the UK’s leading haematologists, isolating the gene that makes the key “factor 8” protein lacking in many people suffering bleeding disorders.

His discovery led to safe treatments for haemophilia that do not require the use of potentially contaminated donated human blood – the ultimate cause of the infected blood scandal.

But he has been marred by his role in that scandal for nearly his entire career.

At the start of it, he treated haemophilia patients at the Royal Free Hospital in London.

The new treatment at the time was called factor concentrate, made using the key blood clotting factors missing from the blood of haemophiliacs. It was revolutionary.

Infected blood scandal: Experimented on and exploited – the Treloar’s School pupils who ‘lost everything’

Blood service collected donations from UK prisons despite infection risk warnings, documents to inquiry show

Infected blood scandal: Bereaved families say loved ones who died after being contaminated were being ‘used for research’

“It was a huge step forward. And convenience, predictability, ability to give the patients a product he could take around with him and treat himself with,” said Prof Tuddenham.

Prior to concentrates becoming available, severe haemophiliacs would often have to be in hospital weekly having transfusions of a donor patient’s blood plasma to control bleeding that could otherwise be fatal.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

But even in the 1970s, there were concerns about the safety of the new medicines.

Made by concentrating the key clotting factors 8 and 9 from the blood of thousands of donors, any contamination in one would contaminate an entire batch.

The fact the seriousness of that risk was not appreciated at the time haunts his memory.

“The amount of effort that should have gone into inactivating viruses, and which had begun already in the late 1970s and had begun to be effective, simply wasn’t put into it,” he said.

If that had been made, thousands of haemophiliacs would not have been infected with hepatitis C which, we now know many of them were during the 1970s and 1980s.

Read more:

It also would have saved haemophiliacs from a new virus that doctors such as Prof Tudenham unwittingly injected into their veins – HIV.

The virus made it into factor concentrates from US blood donors right at the start of the HIV epidemic in the United States in the early 1980s.

New, safer treatments arrived around 1986 but, by then, “it was too late,” said Prof Tuddenham.

‘I was attending funerals all the time’

By this point, Prof Tuddenham had left the clinic to work full time on the genetics of factor 8, work that would lead to far safer, synthetic treatments.

But he kept in touch with former patients.

“I was attending funerals regularly,” he said.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Prof Tuddenham is not a popular figure among the survivors of the infected blood scandal.

He has defended some of his actions at the time, and those of his colleagues, including the decision to conduct trials on children to investigate the effectiveness of new treatments which doctors knew could be contaminated with lethal viruses.

“Of course you couldn’t justify it now. But could you justify then?” he asked.

“A trial in a human was, at the time, the way to distinguish efficacy. But yes, it’s experimental medicine.

“Hindsight, of course, tells us that that led to a lot of people being infected and a lot of people dying as a result. At the time our balance of risk-benefit was seriously misinformed,” said Prof Tuddenham.

“To have caused this in the process of giving treatment is the worst thing you can imagine.”

It’s the job of the infected blood inquiry to decide what may have been acceptable, or even unavoidable at the time, from what was wrong – even by the standards of the day.

The inquiry is due to publish its final report on 20 May.